|

|

|

||||

|

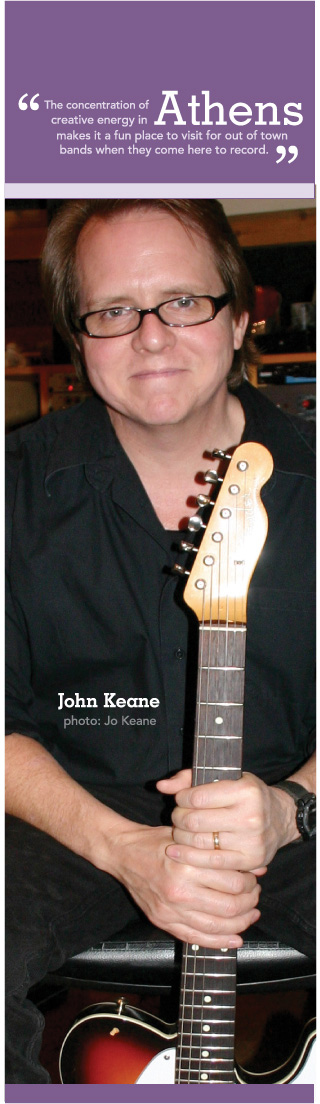

Over the past two decades, thousands of artists and industry professionals have discovered that “vibe.” Georgia’s capital has grown into a hub of Southern sounds with world-class studios, labels and support industries backing its proven reputation as a birth-place of talent. As Atlanta grows, so does Georgia’s music industry. Almost two decades after Antonio “LA” Reid and Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds launched LaFace Records and put Atlanta on the map, the city has grown into a destination for talent from around the world. And behind it all, from neighborhood studios to production companies, is a distinctive Southern charm. The heart of Georgia’s music scene is nestled in a residential area on Antone Street between the areas of Buckhead and Midtown on the outskirts of Atlanta’s downtown. Within a one-mile radius of this row of unassuming office buildings and neighborhood homes, some of the biggest names in music record here at Silent Sound, DARP, ZAC, Sonica and Stankonia Studios. The studios on this street are the heart of the state’s over $1 billion recording and production industry. Atlantans Antwan “Big Boi” Patton and Andre “Andre 3000” Benjamin were one of the first acts to strike gold in the city with LaFace Records. More than 20 million album sales later, the OutKast duo remains in Atlanta where Big Boi owns Stankonia and an independent label, Purple Ribbon. Sitting in her office on Antone Street, Purple Ribbon’s manager Dee Dee Murray said the growth on this little street in the last 15 years is as impressive as it was unexpected. “It’s growing because Atlanta is growing,” Murray said. “It was just word of mouth and it just happened. One act came, then another came, because they had their studios here. It’s where you came to get records made. Now we’re where you come to get hit records made. This is where you come.” What was for years a local scene has grown into a national destination for artists. Murray calls it the “invasion of New Yorkers.” Where once young artists saw New York and L.A. as the only place to make hit records, more and more acts are flocking to Atlanta. Other cities, St. Louis, Memphis, Houston and even Raleigh, N.C., have helped put Southern Hip-Hop on the map, Murray said, but “this is the epicenter.” The music that emerged from Georgia reads like a list of the past 20 years of top-40 radio. OutKast, Ludacris, Jermaine Dupri and TLC were the era’s top hip-hop acts, while R.E.M., The Black Crowes and Collective Soul kept the city’s rock’n roll roots alive. While Athens became world-famous as a mecca for rock talent in the 1980s, Atlanta emerged a decade later as hip-hop’s southern capital. After almost 40 years in Atlanta, entertainment attorney Joel Katz says he now considers it one of the top five music cities in America because creative people can be successful here. “This city has always spawned creative people,” Katz said. “They get their foot in the door because of their creativity, they learn the business side of it, become entrepreneurs and build successful businesses. That’s what we’ve been able to do here.” There’s no better example of this than Atlanta’s own Jermaine Dupri. While he was still a teenager in Atlanta’s high schools, Dupri began producing some of Atlanta’s local talent and, before long, had hits with young hip-hop acts like Kris Kross. That success grew to the point where he was producing and writing for some of the hottest acts in the 90s, like TLC and Jay-Z. He founded his own label in Atlanta, So So Def Records, and is now president of Island Urban Def Jam Records. The hit records made in Atlanta in the 1990s showed it wasn’t just a city where someone could launch a music career, Dupri said, it was a city where they could remain and thrive. “The music movement that we created here made everyone want to be in Atlanta,” he said. “We throw the hottest parties and economically it’s better to be here. It’s hard to tell who is actually from Atlanta these days, so many people are here keeping our scene alive…it’s just the spot.” Dupri’s 2006 classmate in the Georgia Music Hall of Fame was Columbus-born Dallas Austin. Like Dupri, Austin chose to stay in Georgia after finding success with LaFace records in the early 1990s. After winning a GRAMMY® Award and selling millions of records producing TLC, Austin said he and other artists like Dupri believed they could start their own scene in Atlanta. “Ever since we were young, we wanted to see it grow,” Austin said. “We wanted to create our own Hollywood.” Austin attributes Atlanta’s success to its variety of sounds. Other music scenes like Detroit’s Motown established distinct sounds that artists were almost expected to imitate. That’s never been the case in Atlanta, he said, where the acts have remained fresh, the sounds unique and the genres diverse. “We did everything as individuals so we all have different sounds,” Austin said. “You weren’t trying to fit what somebody was looking for. If someone has a hit in New York or L.A., they want you to try to duplicate it.” At his Antone Street studio, Zumpano Audio Company (ZAC), Jim Zumpano said there was always talent in Atlanta, but no labels and distributors. So the moment artists were discovered, they left town. That changed with LaFace. “Hearing LaFace on the radio changed the face of the whole city,” Zumpano said. “They brought real records to Atlanta.” When Reid left Atlanta to head Arista Records in 2001, some questioned the survival of the city’s music boom without LaFace. However, smaller independent labels filled the void, and much of the talent stayed behind, realizing they could keep their roots in Atlanta. When asked why, Murray jokingly attributes it to sweet tea. In the business for almost two decades, Murray said there’s definitely a more hospitable, relaxed vibe about Atlanta. “What makes it wonderful to work here is that we’re competing, but it’s a tight circle for those of us who came up in it,” Murray said. “We see each other at parties. We share employees. It’s a great working environment. It’s not cut-throat like California or New York.” In the music industry, success breeds success. Artists are inclined to stay or move to an area where there is already an established group of artists and industry professionals. Musicians know that there is enough recording and production taking place that they can find the support they need for a project. In turn, more experts and production specialists will migrate to a city where they see enough talent for a steady stream of projects. That’s how other Georgia cities built reputations as bona-fide “scenes” in decades past, from the college rock in Athens, to the Allman Brothers southern rock era of Macon’s Capricorn Records. While Georgia and its capital have always had a reputation for world-class musical talent -- from Little Richard and Otis Redding to OutKast -- the music support industry has caught up with the performers over the past two decades. The growth is reflected in dollar signs. The music industry in Georgia employs about 12,000 people and generates almost $2 billion in economic impact for the state. “There’s more activity in music production, which would suggest more people are coming here to produce,” said Sally Wallace, one of the study’s authors, and Professor of Economics and Associate Director of the Fiscal Research Center at Georgia State University. Zumpano has seen this growth first-hand, watching Antone Street grow from the home of one studio to the center of Atlanta’s music industry over the past 20 years. “It was just a beautiful place for musicians to come to -- not a corporate place and that was very fresh,” Zumpano said. “People loved it because it was a whole different atmosphere. John changed the whole model. You could see it right away: this is where you want to hear and play music.” Musicians and production people were in and out, doing commercials and hanging out and the next thing you knew, Zumpano said, another studio opened and Antone Street became the scene. Zumpano worked as a technician in some of these studios before opening ZAC in 2000. It’s also in a converted house that’s complete with the creature comforts of a living room, kitchen and a wide-screen TV. Zumpano built the studio after years working as a technician on Antone Street and recently celebrated the studio’s sixth year with a concert and barbecue. That neighborhood, cooperative spirit is why Atlanta thrives. “That’s just the way Atlanta is. Nashville’s the same within their circles, but they’re vicious. It’s been a common comment for 10 years when guys come in from New York or L.A.,” Zumpano said. “‘Man, you guys share.’” An hour east of Atlanta in Athens, Georgia, the city’s music industry is kept alive in John Keane Studios located in an 80-year-old home within walking distance of the University of Georgia. Keane engineered six R.E.M. albums and several singles, and recently recorded the B-52s and Widespread Panic in this small house with a swing on the porch, nestled in the town’s historic district. “The residential feel of the studio is very intentional,” Keane said. “I always disliked working in studios that looked and felt like doctor’s offices. I think it’s important for creative people to be comfortable and relaxed when making a record.” Keane grew up in Athens and got his start recording homemade demos with bandmates and friends in the 1980s. There were no studios to speak of, so he started charging some money and buying better equipment and created his own studio. Some of his “friend’s bands” were the likes of R.E.M., Widespread Panic, the Indigo Girls, Dreams So Real and Vic Chesnutt. Keane never wanted to live or do business in the big city, he said, and his hometown had its advantages. “Most of the musical activity is concentrated on a relatively small downtown area, and there is a wide variety of music venues and great restaurants to choose from within walking distance,” Keane said. “The concentration of creative energy in Athens makes it a fun place to visit for out of town bands when they come here to record.” A short drive from Antone Street, Paul Diaz employs the same down-home philosophy at Tree Sound Studios on Peachtree Industrial Boulevard, in Norcross. There’s sort of a coffee house vibe, with couches and kitchenettes scattered around the building sharing space with sound rooms and mini-studios. In the lobby, gold and platinum records by Elton John, Matchbox 20, OutKast and Usher share space with brown, earth-tone paintings. A rehearsal room even includes a 20-foot climbing wall. “We’re different,” Diaz said during a personal tour of Tree Sound that paid as much attention to a solar-powered water heater as to records on the wall. “People need a space to be creative and relax. Happy people make better music.” Diaz started the studio almost 20 years ago with some second-hand audio equipment stored in an Isuzu Trooper and $10 worth of business cards. He got his first business recording local musician friends from Atlanta in his parents’ basement in the Atlanta suburb of Dunwoody. In a few years his equipment collection included a world-class control panel he bought second-hand. By the early 90s, he had built his own studio as a project for the Art Institute of Atlanta. With access to one of only a handful of studios in a town that was about to explode with music over the next decade, Diaz was suddenly booked a year in advance. He saw then, that there was a future for music in Atlanta. One early client was an unknown Atlanta act that called itself OutKast. “At that point, it was a legitimate business,” Diaz said. “I had the option of going anywhere I wanted. I wanted a world-class studio, and I was looking at other states, Austin, Nashville, New York, the West Coast. But you had no guarantee the business would survive. In Atlanta, few people were competing on that scale.” One of those few was Southern Tracks. The late Mike Clark built one of the city’s first world-class studios in Atlanta in 1984. Throughout the 1990s, Clark was recording and mixing major headliners from Pearl Jam, Black Crowes, Stone Temple Pilots, Korn and Limp Bizkit to Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen and Aerosmith. Clark sent Diaz his overflow business for years. And when it came time for Diaz to build his own professionally-designed studio for Tree Sound, Clark had a word of advice. He told him he was crazy for building it in Atlanta. But after scoping out other locations throughout the country, Diaz said the competition was just too steep in more established music cities. Atlanta’s economy was booming, and there was something happening at local clubs. “In Atlanta, hip-hop was starting to blossom and Atlanta was growing. I saw big projects record here but mix in another city. I found people were actually leaving town who might stay in this town. I knew people here. I had connections. I don’t think I could have made it in another city.” Despite Clark’s warning, Diaz’s new studio location on Peachtree Industrial proved a great decision. In his first few years, his clients included R.E.M., Collective Soul, Matchbox 20, Usher and Goodie Mob. “Before we were even open, TLC was in the studio doing vocals while we were still sanding the glass,” Diaz said. In a game room at his office, Diaz keeps a fitting trophy to the success he’s found in Atlanta: a vintage Captain Fantastic pinball machine from the movie Tommy, signed by none other than Captain Fantastic himself. Elton John recorded his “Peachtree Road” album at Tree Sound in 2004. Having icons like that in your studio says something about Atlanta. It’s no longer a city for the music industry’s up-and-comers. It’s an established music city. “At this point we’ve done enough gold and platinum records for years that people know our reputation,” Diaz said. “Thousands of people passed through here and most of our clients are repeat customers. But we still get overlooked all the time because there’s so many things going on in Atlanta. There’s major things happening here.” Started by Luther Randall III in the early 1990s, Crossover consists of a 20,000-square- foot building that’s now one of the major rehearsal studios in the Southeast. Artists like R.E.M., TLC, Arrested Development, Toni Braxton and Keith Sweat to Elton John and Shawn Mullins have used its large rehearsal studios to prepare for tours and choreograph their stage acts. Recently, Crossover hosted Janet Jackson, New Edition and the Gin Blossoms for rehearsals. The studio also keeps a warehouse of drum kits, guitars, keyboards, microphones and sound equipment for lease to bands hitting the road. Randall operates his family’s building supply company but an interest in live music and friendships with local musicians gave him the idea of an entertainment support company. Major acts were either coming out of Atlanta, or passing through Atlanta on tour. They needed equipment and a place to rehearse. “When we started, the timing was great because LaFace and Baby Face came into town looking for talent,” Crossover manager Billy Johnson said. “We offered a place for them to grow that talent.” Johnson credits music’s success here for the same reasons other businesses call Atlanta home -- its accessibility. It’s home to an international airport, great restaurants, hotels, major league sports with giant arenas and great concert venues. Other cities have those advantages, but they’re typically much larger than Atlanta. “Try parking a tour bus in New York City,” Johnson said. And it has charm. “Atlanta’s just a friendly town,” he said. “People make a customer one at a time and there’s tons of talent. Just look at OutKast. They could live in L.A. or New York, but they have a lot of loyalty and respect for people here. We couldn’t do this in just any town.” With labels, studios, rehearsal facilities and everything needed to sustain a professional acts, Johnson said Atlanta has entered a period of stability. LaFace Records left in the late 1990s but Atlanta and Georgia have proven the forecast is for steady continued growth. “Because the movers and shakers are living and staying here, it’s a place to do business and it’s still growing,” Johnson said. What’s next on Atlanta’s music horizon? Many producers are moving into film. With large studio sets like Crossover capable of staging commercials and music videos, the goal is to try to gain more of a foothold in the film industry. Georgia already has a $500-million-a-year film, commercial and video industry, and six major feature films and 15 indie features were shot in the state in 2006. More than 70 TV episodes were shot here, and 46 music videos during the same time period. “Several of Georgia’s music producers are crossing over into producing feature films,” said Bill Thompson, director of Georgia’s Film, Video & Music Office. “Local composers who once primarily scored films and commercials are now composing music for Georgia’s video game industry.” Austin was executive producer of 20th Century Fox’s 2002 film Drumline, based on halftime performers at historically black southern colleges, and said he wants to see more feature films shot on the streets and back lots of Atlanta. Austin also was one of the producers of the Warner Bros. feature film ATL in 2005. Producer Antwan “Big Boi” Patton has formed a film production company called Purple Ribbon Entertainment. It’s part of that goal of creating Georgia’s Hollywood. |

|||